July 26, 2023 at 8:00 a.m.

By Lee H. Hamilton

All eyes were on NATO last week as leaders of its member nations met in Lithuania to debate key issues, including their response to Russia’s war against Ukraine. That marked quite a change – a positive one — in the status of the 74-year-old organization.

Just a few years ago critics were writing NATO off as an institution that had served its purpose. The Soviet Union, its old nemesis, had collapsed. Donald Trump, as president, bashed NATO allies for not carrying their weight and reportedly threatened to pull the U.S. out of the alliance. French President Emmanuel Macron famously remarked that NATO was experiencing “brain death.”

But everything changed on Feb. 24, 2022, when Vladimir Putin sent Russian troops into Ukraine. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, writing recently in Foreign Affairs, called the invasion “a turning point in history.” Now there was no question about NATO’s relevance.

The alliance has been the framework for nations to oppose Russian expansionism, and the United States has played a leadership role. While Ukraine isn’t yet a NATO member, it sees a revitalized alliance and deepening Western cooperation, as the WSJ notes.

At the summit in Lithuania, NATO members agreed to what Stoltenberg called a “strong package” of support for Ukraine, including a multi-year plan for strengthening Ukraine’s military, creation of NATO-Ukraine Council to consult on issues, and a pathway for Ukraine to become a NATO member. President Joe Biden, in a speech at the end of the summit, praised NATO unity and said Putin is “making a bad bet” by doubting its staying power.

NATO was created in 1949, in response to the devastation of Europe caused by World War II. An estimated 36.5 million Europeans had been killed and millions were displaced. There were real concerns that national rivalries would reassert themselves and another war would break out. The Soviet Union posed a clear threat.

The NATO treaty bound the initial 12 nations to mutual self-defense, declaring that an attack on one would be considered an attack on all. The pact deterred Soviet aggression and did so without warfare. NATO has rightly been called the largest and most successful military alliance in history.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, NATO focused on terrorism, ethnic violence and civil war. It grew to include dozens of nations, several former Soviet republics among them. But, under Putin, Russia stepped up its aggression, fighting with the Republic of Georgia and Chechnya separatists and annexing parts of Ukraine, including Crimea, in 2014. When Russia troops drove into Ukraine proper last year, a line was crossed.

More nations sought NATO membership and the security it would bring. Finland, a formerly nonaligned state that shares an 830-mile border with Russia, became the 31st member this year. Sweden will soon become No. 32 now that Turkey has dropped its objections.

Ukraine, for obvious reasons, is eager to join as well. In the leadup to last week’s summit, Zelensky expressed impatience and said NATO’s criteria for membership were vague and “absurd.” But with the promise in Lithuania of more support, he appeared to be satisfied.

NATO has worked hard to project unity. That may be hard to maintain. Europe has relied on Russia and Ukraine for energy and food, and the war has had economic consequences. Some NATO countries, particularly those in Russia’s shadow, were ready to admit Ukraine to membership now. The U.S. and other members have been cautious, concerned that admitting Ukraine could provoke a wider conflict with Russia.

These kinds of disagreements among friends are to be expected in any large alliance. What’s important is that NATO members work through them and stay focused on our common interests. A strong and unified NATO has made the world safer for almost 75 years. We must work so that it continues to do so.

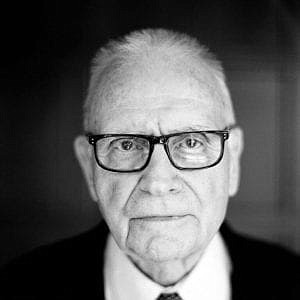

** Lee Hamilton is a senior adviser for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government, a distinguished scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and a professor of practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.