June 16, 2023 at 7:10 a.m.

By Lee H. Hamilton

There are so many things I worry about these days. Are we going to default on our debts? Can we adapt to the accumulating impact of climate change? How are we going to handle the dangers posed by China and Russia?

But bigger than all of those is this: Can we as a nation confront those challenges by arriving, together, at reasonable solutions? Or to put it another way, do we even know any more how to carry on a public dialog about the issues we face and how to resolve them?

Because I worry — a lot — that we’re losing our ability to engage in the reasoned dialog that democracy demands of us. The evidence surrounds us: the hot-tempered dogmatism that’s rampant on social media, the take-no-prisoners rhetoric of cable commentators, the shallow political debate carried on by everyone from pundits trying to gin up an audience to politicians who should know better, the widespread impatience with others’ viewpoints, the shrill and even offensive language that permeates public debate … You know the problem as well as I do.

And it is a problem. If Americans lose faith that our democracy is up to the task of addressing our challenges because we’re incapable of holding a discussion that isn’t distorted by spin, misleading studies, grassroots manipulation, untrustworthy media, and political leaders who wouldn’t publicly recognize a fact if it smacked them in the forehead, then the travails of the last few years will seem like a cakewalk.

So I have some suggestions. Because in the end, if we want the quality of public dialogue to improve, then it’s up to us to improve it — and then let our political leaders know that we expect more than political posturing that produces inadequate solutions to difficult problems. Living in a democracy takes work, and that applies to all of us, from voters who cast their ballot every few years to neighbors who roll up their sleeves and try to improve their communities to elected officials whose job it is to decide the course of their town or state or country.

Here are a dozen basic principles we need to keep in mind:

1. Don’t fear differences or dissent. They’re inevitable, and they are vital to looking at challenges from all sides.

2. Advocacy and even conflict have their place in a democracy, but in the end, we resolve differences and break gridlock through discussion and deliberation.

3. Which means that the goal is not to highlight or inflame our political differences, but to resolve and reconcile them. The highest good should be to search for compromise, where everyone is at least a partial winner.

4. Remember that political differences may be stark, but that doesn’t mean they’re irreconcilable.

5. Focus on facts. They’re the starting point for levelheaded debate and effective policy. As citizens, it’s our job to find trustworthy sources of information, question our own biases, and discern when we’re being misled; as politicians, to strive always to seek the truth about the facts.

6. View one another as neighbors, fellow community members, or colleagues who all want the same thing: what’s best for our country and for where we live. Find common ground and build trust from there.

7. It is always worth the time to understand others’ viewpoints — and to talk. You may not just find common ground, but ways to improve your own ideas.

8. And when you do search for commonalities, talk about common concerns first and differences second.

9. Focus on the common good.

10. Do not speculate on rivals’ motivations or demonize them. Focus on their ideas — and see them as just as human as you are.

11. Sometimes drama can be effective, but always maintain civility and convey respect for people who think differently from you.

12. Finally, always keep in mind that you may be wrong. The world is complicated and solutions to its challenges are never perfect or straightforward.

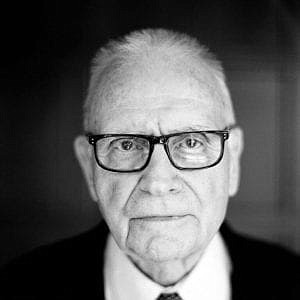

** Lee Hamilton is a senior adviser for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a distinguished scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a professor of practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.