September 19, 2023 at 8:35 a.m.

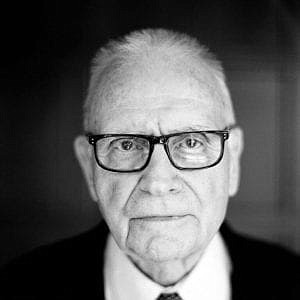

By Lee H. Hamilton

One of the hardest things to watch as Congress has evolved over the past decade or more is the extent to which its oversight muscles have atrophied.

Sure, committees on Capitol Hill still haul members of the administration in front of them to ask uncomfortable questions. But while there has always been a tinge of theater to the practice, these days it often seems to be mostly about the show — and in particular about scoring political points — and not so much about helping our government operate effectively.

To be blunt, this is a waste. I’ve always believed that what our founders had in mind was to encourage a creative tension between the president and Congress that would inspire constructive policy-making and produce government action in the nation’s best interests. Oversight is Congress’s chief tool for achieving this.

One big reason is that making government work well is tough and always has been. Even when accomplished officials are doing their best, they can struggle to ensure that their agencies and programs are being both efficient and effective, not to mention hewing to what Congress intended. Congress’s job is to look into every nook and cranny of the executive branch, pay attention to what’s being done in the people’s name, weigh whether it’s the right course, and, if necessary, legislate improvements.

But there’s more to it than that. I’m not suggesting Congress should directly be involved in the management of federal programs, but it does have a responsibility to ensure that the president and his administration are operating in ways that serve US interests, take into account public sentiment, and meet a very high standard for prudence, foresight, and even wisdom.

My knowledge on this front lies with foreign policy, thanks to several decades serving on and then chairing the House Foreign Affairs Committee. One of the things I tried to do in hearings, both at the subcommittee and full committee level, was to ask policy makers to articulate their approach and then to defend it. This was neither a simple nor a quick task, since the core idea is to give the people creating US policy a platform to lay out their thoughts and explore the details — which in my experience often meant extended hearings. I wanted plenty of time to delve into the policies themselves, and then to hear how officials defended them.

This meant asking a series of questions. What was the policy itself? What were its objectives? Its strengths and weaknesses? The risks involved? If the policy an administration is pursuing succeeds, what will the world look like a year from now, or two years, or five? And if it’s put in place successfully, what will the US itself look like a few years down the road? How will American interests be served? If we’re talking about foreign policy, how will it affect US standing in the world? And if it’s domestic policy, how will it affect the quality of life in this country?

These are all questions you’d hope public officials ask themselves as they’re formulating policy. Sometimes, they do. But it’s not a given, and it’s Congress’s job to ensure those questions get asked and answered.

There’s great power in this. Good oversight can repair unresponsive bureaucracies, catch mistakes, encourage course corrections early in the game, expose misconduct, lay bare incoherent or chaotic thinking, avoid failure, and help policy makers improve their game for the next time. It takes effort, expertise, and a deep interest in helping the US government succeed, whoever’s in charge.

In the end, robust congressional oversight is about ensuring that government can meet its challenges while at the top of its game. It would be nice to have a Congress that thought so, too.

** Lee Hamilton is a senior adviser for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a distinguished scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a professor of practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.