April 15, 2024 at 8:30 a.m.

Lost treasure can be buried deep, maybe in the depths of an ocean, but sometimes the riches are hidden in boxes and crowded drawers, in closets and trunks, and in the darkness of attics beneath the dust and cobwebs. Occasionally they rest almost untouched in the belongings of loved ones.

Two years ago, I delivered a collection of letters (1925-1930) to an Earlham administrator for my sister Linda. Written by a Quaker missionary in Ramallah, they had not been read for forty years but were invaluable to the Friends college. The professor noted that history was often captured in journals and diaries and letters. He enjoyed hearing from families who stumbled across the past.

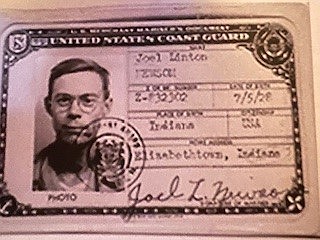

Coincidentally, I just finished a 1946-1947 journal kept by Joel Linton Newsom that was shared by his son Ross. I met Joel when he was 40 and I was 14. I knew Joel the Jokester, a man who could laugh his way through a story and polish it with a smile. I did not know Joel the Sailor who was involved in a forgotten part of WWII history. Joel was a seagoing cowboy.

From 1945-1947 the Church of the Brethren, along with Mennonite and Quakers, donated livestock to a war-torn Europe. Young men from those faith communities volunteered to care for the animals that were given freely to European countries. Food was provided. Farms were replenished. Wikipedia states, “These seagoing cowboys made about 360 trips on 73 different ships.” The farm boys who signed up were known as seagoing cowboys.

Joel Newsom was a Quaker who graduated from Columbus in 1946. In August a Western Union telegram directed him to report to Newport News, Virginia for his assignment in the humanitarian, Coast Guard adventure. He passed many civil war sites along the way, none that probably prepared him for the battlefield in Poland he would see in September. It would be October before he returned home.

Joel served on the Michael J. Monahan, a liberty ship. It would take 15-28 days to cross the Atlantic. Although chickens and cattle were mentioned, horses were the main cargo. Of the 804 horses on board, 33 died. The rest were delivered to feed the hungry. Joel wrote very little about the animals. He wrote more about the sights and experiences that were uncommon to him.

Early on “most of the cowboys got seasick, including me,” he said. When he was sick, he recalled a poem:

My breakfast lies over the ocean

My lies over the sea

My tummy’s in a commotion

And please don’t mention supper to me

Joel mentioned that even green sailors learned where to hide from work. He did not appear to be a smoker but recognized the value of cigarettes for bartering, especially in Europe where he would pick up a good camera for twenty cartons. At the “Slop Chest,” the ship’s store, he was more likely to buy candy. A midnight snack was appreciated. Having extra when the store netted him almost fifty dollars profit.

He saw seven countries: England, France, Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and Poland. Children ran alongside the ship in the European canals asking for candy and cigarettes. Joel mentioned only one day on the trip that was work-free. Multiple times he expressed disappointment that there was no Sunday service.

In Poland he shared that the cowboys did not want to be in the city at night. The Russians were said to shoot and then ask questions. He complained that as they arrived in Europe the meals grew smaller. Later, on the trip back home, he had an opportunity to sunbathe. He discovered that his swimming suit didn’t fit. His 135-pound frame had dropped to 120.

As they neared the delivery destination a storm caused mines to surface. Another ship was damaged, and a dead body floated by. A guide took them to a battlefield where tanks and artillery and bodies littered the landscape. Joel looked for a souvenir and wanted a helmet. He nearly fainted when the one he picked up had a head in it.

Many of young cowboys grew beards, but Joel settled for a “nose scrapper.” He learned to play cards. He was “homesick to get on something that didn’t rock forever.” Thousands of miles from home he met Charles McCraken who knew Joel’s sister Doris at Earlham. He lit a cup of vodka and was sure that “a car could run on it.”

What I didn’t read was that an 18-year-old cowboy truly understood the impact of his effort to help people. He wrote about daily activities, about moments that were different than those experienced in Sandcreek township, and about life on a ship. Didn’t Joel grasp what he and the boys on the other 359 trips had sacrificed to help others?

Actually, I think he did. Maybe his actions captured that he understood the value of the trip better than his words did. In June of 1947 he signed up for a second voyage. This commitment paid $125 dollars. It was not sponsored by the Church of the Brethren, but it was another effort to help others. Sometimes young people just do what needs to be done. Do we ever treasure that enough?