August 24, 2024 at 9:20 a.m.

By Lee H. Hamilton

We’re less than 100 days away from a presidential election that many Americans consider the most consequential of their lifetimes.

So, it’s hardly surprising that most of the attention in the runup to November is focused there. But I’m here to make a plea: Pay attention to congressional and legislative contests, too.

I say this not out of some civic do-gooder belief that all public offices matter, but because what happens in this year’s congressional and legislative races will have very real consequences for this country’s direction. It matters who gets elected president and governor. But it matters just as much who controls the legislative bodies they have to work with.

Let me draw from my own career to explain. I first went to Congress nearly 60 years ago, in 1965. The 89th Congress was controlled by Democrats in both chambers, and there was a Democratic president, Lyndon Johnson. Together, they produced what’s been hailed as possibly the most successful Congress ever. In all, 810 bills were enacted, including the creation of Medicare and Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, the Older Americans Act, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Higher Education Act, the Water Quality Act, the Freedom of Information Act, the Highway Safety Act, the Financial Institutions Supervisory Act, and more. It’s fair to say that the US was a safer, more equitable, more opportunity-laden place when we got done than before we started.

The last Congress I served in was the 105th, which ended in early January 1999. The contrast couldn’t have been starker. A Democratic president, Bill Clinton, spent the years of the 105th confronting a Republican-controlled House and a Republican-controlled Senate. Not surprisingly, much less got done. There were 394 bills enacted — fewer than half the number of the 89th. In a newsletter to constituents at the time, I wrote, “The 105th Congress did have some significant accomplishments” but overall “the legislative record of the 105th Congress was meager. Only a limited number of important measures passed, many key initiatives died, and the leisurely pace meant fewer legislative days this year than any in memory. Most agree that Congress left town with a lot of America’s business unfinished.”

You don’t even have to tally legislative accomplishments to understand how House and Senate elections matter. Eight years ago, after the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, President Barack Obama tapped a centrist, Merrick Garland, as his choice to replace Scalia. But Republicans controlled the Senate and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced that the Senate would not confirm any appointment by Obama; instead, it would wait until the next president put forth a nominee. You know what happened: Donald Trump won the presidency and filled the seat with a conservative, Neil Gorsuch. The course of the last eight years would likely have been quite different had Garland been seated.

Which brings us to state legislative elections. One obvious consequence of the conservative majority on the Supreme Court has been a sharp decline in the availability of abortions and reproductive health care nationwide in the wake of the Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision undoing Roe v. Wade. In all, 22 states now completely ban or severely restrict abortions. Meanwhile, 20 other state legislatures have acted to add new protections to abortion rights. This is a function of who controls the legislatures (and governorships) in those states. You may be pleased or alarmed by the direction your state has moved in the two years since the Dobbs decision, but it would be hard to argue that state legislative elections don’t matter.

So, before you go to the polls this year, pay attention to the candidates who are running for Congress and the legislature: what they stand for, the policies they want to pursue, how serious they are about governing. And pay attention, too, to what you want to see happen: If you want our next president or your next governor to get a lot done, you’ll want to see a congressional or legislative majority of the same party. If you don’t want much to get accomplished, you’ll favor an executive dealing with a Congress or legislature of the opposite party. Either way, your down-ballot vote will matter.

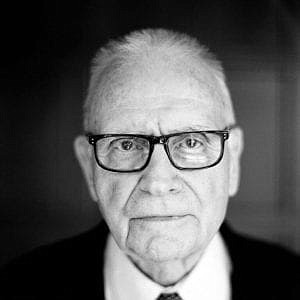

Lee Hamilton is a senior adviser for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a distinguished scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a professor of practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.