May 9, 2024 at 12:10 p.m.

By Lee H. Hamilton

There was lots of drama back at the end of March, when Congress — six months behind schedule — finally funded the federal government for the rest of the fiscal year. You may remember some of the highlights: The $1.2 trillion package funded defense, homeland security, and other key agencies (others had gotten their funding a few weeks earlier) and Congress passed it mere hours before a government shutdown.

This, of course, was characterized as a great success, though Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, a Democrat, was straightforward about what it took. “It’s been a long day, a long week and a very long few months,” he told the press. “It’s no small feat to get a package like this done in divided government.” Over in the House, the fact that Republican Speaker Mike Johnson played ball with Democrats to get the package through led to the first stage of a move by Rep. Marjorie Taylor Green to seek his ouster as speaker.

I take no comfort at all from the fact — indeed, I’m genuinely outraged — that we’re just going to go through all this again at some point down the road. The congressional budget process is deeply and fundamentally broken.

What I find most distressing is that there’s now an entire generation of Americans and members of Congress who know only this: that the budget consists of a gargantuan bill hammered out by congressional leaders and the White House and some key staff, then is rushed through with very little debate and even less insight into what it contains, other than some key topline figures. The fact that in the world’s greatest democracy this is how we handle the fundamental blueprint of our government, and its priorities should not be a point of pride. As veteran budget analyst Alice Rivlin put it, it is “frightening and embarrassing that the world’s most experienced democracy is currently unable to carry out even the basic responsibility of funding the services that Americans are expecting from their government.”

That was in 2018, the year before her death.

That’s especially true because we know how to do better. Though I’ve done this before, let me remind you of what you’re missing.

Up until the mid-1990s, Congress followed a process that had been honed over decades. It divided the budget into a dozen different areas, and then handled their appropriations through separate committee hearings. These allowed committees — and the rank-and-file members who sat on them — to gather expert opinions, propose changes, and thoroughly vet federal spending decisions in both chambers before sending each bill on to the president. It was not a perfect process, but it was transparent, far more democratic, orderly, and a politically rational way to decide on our priorities and how to fund them.

These days, we just take it for granted that we have to live with high-stakes fiscal brinksmanship. And that the myriad crucial decisions that undergird our government’s operations will be contained in omnibus spending bills or continuing resolutions that basically put the government on automatic pilot and get no real scrutiny. Congress’s historical role as a nurturer of innovation and creative approaches to problem-solving? Nowhere in sight.

I don’t know what it’s going to take to improve matters. There are plenty of members of the GOP majority in the House who ran two years ago on restoring the “regular order” of the appropriations process. And in all my conversations with public officials in recent years, I’ve never heard a single one defend what goes on now.

Members of Congress are now working on the next appropriations round, facing an Oct. 1 deadline to keep the government funded. It’s an election year. Any bets that they’ll get the job done in orderly fashion and without resorting to a stopgap spending measure in September? I didn’t think so.

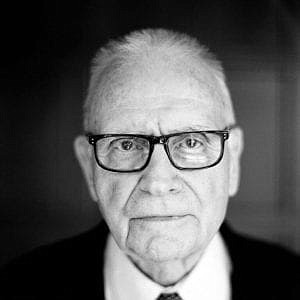

** Lee Hamilton is a senior adviser for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a distinguished scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a professor of practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.