May 26, 2024 at 9:10 a.m.

By Lee H. Hamilton

I’ve either been involved in or keeping an eye on American politics for more than 60 years now. We’ve faced plenty of tough questions during that time, and though many of them have been resolved and we’ve moved on, some are tenacious — income inequality, racial equity, the ever-ballooning national deficit, climate change. But in all those years, the question I’ve found myself returning to again and again — and that I suppose we’ll never really resolve — is the one Lincoln posed at Gettysburg: Can a nation like ours, ‘conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,’ endure?

He asked that question in 1863. Here we are, 161 years later, and it’s still pertinent — perhaps more so this election year than any other in recent memory. Yet when I think about what Lincoln said, what always strikes me is what he didn’t say. He did not call for replacing what was then still a relatively young representative democracy with something else. He didn’t say, “Our system’s being tested and we’re going to have to jettison it to meet the challenge.” He called, instead, for redoubling our dedication to the experiment our founders embarked upon.

It was a reminder at a very dark time in our history that representative democracy is a never-ending work in progress. The issue of whether it can endure is always in doubt. The question that we face as Americans isn’t whether something would be better for us. It’s how we can make it work.

Today, truly systemic problems are challenging ours and other democracies: all kinds of discrimination, unevenly distributed economic rewards and uncertainty, political polarization, misinformation, the degradation of civic discourse. But we’ve faced tough challenges in every generation: wars, recessions, civil unrest, economic disasters. We’ve always squared our shoulders and returned to what unites us: our democratic ideals and our beliefs in our basic rights, fundamental freedoms, and shared responsibility for making it all work.

The greatest risk in all this is that if we don’t pay attention or we become complacent — if we as Americans disengage — then we place in jeopardy the democratic enterprise Americans have spent two and a half centuries shaping. Our freedoms and our rights can, without question, be eroded.

So what do we do? This may seem fuzzy, but I think it’s anything but: We have to renew our appreciation for being part of the American republic. Let me put it this way: We live in a political system marked by strong, independent branches of government, each designed to exercise limited and defined powers within constitutional boundaries. We have checks and balances, separation of powers, individual rights and opportunities, rule of law, and fair and free elections overseen by an army of election workers who are our neighbors. This is a monumental achievement that can always be improved, but that always gives us room to seek a more perfect union. And we’ve thrived as a result.

People often ask me whether I’m pessimistic or optimistic about the future, and it’s a question I resist answering, because it doesn’t matter. What does matter is that whatever the challenges we face, we accept them and use the system and its endless possibilities to address them. Our strength comes when we recognize that we’re all in this republic together and work cooperatively for a country in which all persons have an opportunity to enjoy the promise of America and to live a life of honor and excellence.

In the end, we have no choice but to step up to our responsibilities as citizens. And to ensure, time and time again, that, as Lincoln put it at the end of that short speech, “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

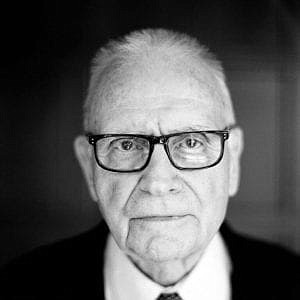

** Lee Hamilton is a senior adviser for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a distinguished scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a professor of practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.